While it is too much to claim that environment determines culture1, it does not seem unreasonable to assert that the conditions in which one lives should have at least some effect. Take, for example, a curious fact of Canadian marriage law. As you know, Canada has an average population density of just four people to the square kilometer. Thus, the legality of marriage between cousins. Otherwise a Canadian might have to walk a great distance to encounter someone to whom they were not related2.

Even if environmental determinism is complete bollocks, assuming it’s a real phenomenon can result in some interesting plots when it comes to writing fiction—as demonstrated by the following tales.

Crisis on Conshelf Ten by Monica Hughes (1975)

Environmental determinism shapes the two communities featured in Conshelf, undersea cities and the Moon.

The undersea communities—remember when submarine cities were going to be a thing?—are surrounded by an environment that will destroy them if they aren’t unceasingly careful. But this takes money, which the land-dwellers who own Conshelf Ten are reluctant to supply. Unhappy Conshelf residents are plotting a revolution.

Protagonist Kepler Masterman is visiting from the Moon, an environment which is even more hostile to human life than is the ocean. Although his Lunar community is largely off-stage, we learn two things about it that underline how much their culture has been warped by their environment. Because all must work hard to sustain the fragile Moon colony, there’s no room for unproductive residents. When Kepler’s father has to travel to Earth, Kepler must follow his sole parent3.

We also learn that the colony has decided that love marriages might lead to destructive social conflict. Again, apparently due to the razor-thin margin of survival on the Moon, the parents don’t think the community would survive discord, so kids are assigned their future spouses at age thirteen and married at eighteen. Kepler is betrothed.

I suppose the Moon is such a harsh mistress that it should not be surprising that that its customs are very different from Canada’s (where Hughes lived). Presumably there are other social side effects from the Lunar perception that the colony is one argument away from disaster. To be honest, nothing that Kepler says about his home gives the impression of a community able to survive a serious setback.

Sight of Proteus by Charles Sheffield (1978)

For the most part, Sight of Proteus concerns itself with Form Change (biofeedback-controlled shape-shifting) and the ramifications that some applications of the process have on the effort to keep an overpopulated Earth functioning.

I could argue the various curious cultural adaptations found on overpopulated Earth are determined by the precarious environment. I won’t. Instead, I will focus on the curious behavior of the novel’s Spacers.

You might expect that Spacers, the embodiment of human destiny, will embrace technological experimentation. Sheffield’s Spacers do not. This is because, living in a dangerous environment as they do, Spacers prefer old but reliable tech to shiny new tech. This conservatism does not always work in the Spacers’ favor, but it does keep down the death rate.

I am reminded of a comment from Star Cop’s4 Nathan Spring:

“You leave Earth and anything you forget to bring with you will kill you. Anything you do bring with you which doesn’t work properly will kill you. When in doubt, just assume *everything* will kill you.”

Way-Farer by Dennis Schmidt (1978)

Only after a one-way trip to the surface of Kensho did human colonists discover their seemingly perfect world had an undetected flaw5. Invisible, immaterial entities the colonists nicknamed Mushin inflamed emotions. Eighty percent of the colonists died as minor irritations escalated into homicidal violence.

Why or how the Mushin do this is unknown. What is known is that people of faiths that encourage self-control, Zen Buddhism in particular, had a much higher survival rate than people of different backgrounds. Unable to leave Kensho, the surviving settlers had no choice but to embrace austere, extraordinarily moderate behavior lest the Madness strike again. That will buy time, but perhaps not survival.

In one of those extraordinary coincidences one sees in fiction from time to time, it seems that this novel of martial arts and Zen Buddhism, where to stray from the Path can mean an unpleasant death, was written by a man who was himself a martial artist and Zen Buddhist.

This World Is Not Yours by Kemi Ashing-Giwa (2024)

Amara and Vinh have chosen the New Belaforme colony as a refuge from interfering family because it’s so far away in space and time. Vexatious family members will be long dead by the time the lovers arrive at their destination6.

Life in New Belaforme is shaped by a more immediate concern. The fledgling human colonies share the planet with a pervasive phenomenon called the Gray. The Gray appears to be an environmental guardian. It is of the utmost importance that settlers avoid convincing the Gray they are an invasive species. The consequences of failure would be calamitous.

Colonizing a planet where a single misstep could doom everyone may seem like a bad idea. It is. However, the organization that arranges such things does not care about the fate of individual colonies. Instead, they opt for settling as many planets as possible in the hope that a few colonies will be profitable.

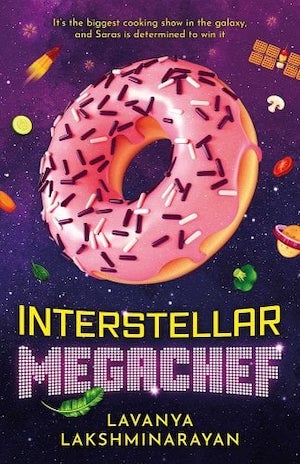

Interstellar Megachef by Lavanya Lakshminarayan (2024)

Saraswati “Saras” Kaveri flees Earth under an assumed name, hoping that victory in the Interstellar MegaChef contest will secure her independence from her family. It’s a bold plan no more unreasonable than basing one’s retirement on the certainty of winning the Powerball lottery and it’s in no way Saras’ fault that her gambit does not work out as planned.

Primus, the planet on which the competition is held and which supplies the judges, was settled by slower-than-light starship. The austere conditions of the initial colony shaped the culinary tastes of its descendants. Food preferences on Earth and Primus have diverged; what is considered supremely tasty on Earth is anathema on Primus.

Primus takes enormous pride in having left behind the barbaric prejudices of backward Earth. One might expect that it would have learned cosmopolitan tolerance and would take differing cultural standards into account when judging food. Primus has not. It cannot transcend the initial environmental determination.

There are, of course, many more works of science fiction in which aspects of environmental determinism play a key role. Please let us know if I’ve missed your own favorite example in the comments below.

- Let’s pretend someone mentioned Jared Diamond and also that we don’t need to spend time debunking him. ↩︎

- It could be argued that this legal quirk is due to the fact that most of the Canadian population lives in one densely populated strip next to the US border. Canadians grow up surrounded by irresistibly attractive fellow Canadians, attraction that suppresses the Westermarck effect. ↩︎

- This odd detail is surely not because the author needed a slender pretext to force Kepler to visit the Earth, but due to the corporations that own the Lunar colonies being short-sighted and cheap. Shortsighted, counterproductive penny-pinching is a running theme in the novel. ↩︎

- Star Cops was a BBC hard SF space police procedural, in which a collection of broad national stereotypes (dour British inspector, dim but determined British plod, criminally inclined Australian, politely deferential Japanese scientist, and so on) attempted to enforce space regulations. ↩︎

- The text is a bit unclear whether the initial surveys of Kensho involved humans on the ground. If the survey team stayed in orbit, exploring the surface via probe, then it makes sense they never noticed the Mushin. If they landed, then they got very lucky. ↩︎

- Unless the loathsome kin immediately jump into their own starship and pursue the errant couple, in which case relativity won’t hinder a confrontation between couple and kin. However, the lovers can be reasonably sure that won’t happen; the kin would end up exiled from their homeworld as well, which would be a high price to pay for such a spiteful quest. ↩︎